“The story goes like this: the paradigm of equal opportunity is a truly objective, neutral, and fair method to allocate educational, employment, and political resources to members of society, without regard to race, class, gender, or ethnicity… I disagree with the conception of equal opportunity as an objective, neutral, natural, and fair principle that enables social minorities to progress in society, limited only by their own ability and free choices. Rather, equal opportunity is an intricate fabrication intended to preserve the status quo and language of the dominant culture through reliance on popular, yet mythical, norms of individualism, sameness, and neutrality. There is no “equality of opportunity” in America, past or present. Further, the language and principles underlying equal opportunity reinforce structures of privilege. In order to move forward in a collective fight against privilege and inequality, we must abandon the existing conceptual framework of equal opportunity.”

– Christian Sundquist. “Equal Opportunity, Individual Liberty, and Meritocracy in Education: Reinforcing Structures of Privilege and Inequality.” Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law and Policy 9, no. 227. (2002).

Opportunity. Everyone believes in it. Everyone believes they all have it. But not everyone has the same level of it. One of the great prevarications of the American society is that everyone has “equal opportunity”. We’ve begun to address the problem in a number of ways. However, we have a long way to go. Equality is a marathon, not a sprint (as it should be) unfortunately. Some seem to think affirmative action has solved the problem, and that racism has ended because we have a black president (I would argue the sheer number of claims that Pres. Obama is from Kenya and how many people referre to our president as an n—-r show alone that racism is alive and well). People of color [POC] are still impoverished and uneducated in overwhelmingly high numbers. Black boys are still dying in Chicago and Compton. White Americans are impoverished too though, make no mistake. White boys in poverty are still being forgotten by the purview of our “equal opportunity”. Poverty does not care what color one is, it will sting all the same.

What does poverty have to do with opportunity? Poverty has everything to do with opportunity. Absolutely everything. Quality of education and nutrition alone are major factors that separate those that have wealth, and those who do not. It’s powerful. A large and, honestly, offensive misconception that is floating around the American psyche is that “poor people don’t work hard enough, THAT’s why they don’t have money.” As if the working poor lack some quality that does not allow them to work hard, or something.

“This is part and parcel of conservative thinking about the rich and poor in this country: that the poor are so because they lack some basic value — ambition, for example — and the rich are so because they have an abundance of it.”

– Charles Blow. “Poverty is Not a State of Mind.” New York Times. May 18, 2014. http://mobile.nytimes.com/2014/05/19/opinion/blow-poverty-is-not-a-state-of-mind.html?_r=0&referrer.

Ah, do they lack ambition? Mr. Blow in his op-ed for the New York Times was on to something. Now, I won’t point my finger at conservatives, that’s Mr. Blow’s words. However, the way the poor/rich dichotomy is taught and perpetuated in American society is troublesome. Scary, even. We have “equal opportunity”, but we think that the poor do not have the mental faculty to be equals to us (that are not in poverty) in our work ethic? The mendacious claims that the poor are lazy are appalling, considering people in poverty spend their whole existence… well, trying to exist. Appalling and troublesome.

“Poverty is a demanding, stressful, depressive and often violent state. No one seeks it; they are born or thrust into it.”

– Ibid. (Charles Blow, New York Times)

People in poverty have difficulty learning, maintaining families, and functioning healthily because it is so demanding, stressful, depressive, and violent to be impoverished. It is incredibly painful emotionally. And I thank my parents every day for keeping me from the experience of poverty. In fact, do that right now. Silently thank your family if you are not in poverty and you have a phone or computer to read this. If you pray, pray to G-d right now and thank Him for not being impoverished. When Mr. Sundquist rejects the framework of equal opportunity, he is partially saying that poverty perpetuated by our institutions is keeping people from equal opportunity. If you are born into poverty, you are already several paces behind someone born in a middle-class family. Okay, maybe a few people make it out of poverty with luck or unwavering dedication, but as John Rawls’ political conception of justice reminds us, we must be concerned with striving for a completely free, fair, and equal society. All Americans need a legitimate equal opportunity in order to be the just society we purport to be, Rawls argues.

Education was supposed to provide “equal opportunity”. It was supposed to be the Great Equalizer. Education has done excellent work of educating individuals for elevating their opportunity and truly allowing them to “follow their dreams”. However, there is quite a bit of handiwork to do. We can begin in the classroom. The classroom, at first glance, seems neutral and safe. It is unless you’re a POC.

“Whites are carefully taught not to recognize white privilege, as males are taught not to recognize male privilege.”

– Peggy McIntosh. “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women’s Studies.” Peace and Freedom. (1989).

White privilege can proliferate into nearly everything in life, but I want to keep the focus on the classroom. White people know their race is represented. They exist. They can fully access their race’s history. That is almost a given in every classroom. They never have to be spokespersons for their own race. They don’t have to answer for what their forefathers did. As a black male, the most unsettling days of class was when we covered Black History. I could feel the awkwardness permeating in the room as the teacher talked about the measly half-paragraph of Malcom X. I could feel the eyes peering at me, as if I was the manifestation of black history. As if I had a PhD in black history. As if the death of white men and the raping of white women were my responsibility in some twisted way. That’s how it feels to talk about black history in a room of white people. I can only imagine the horror of being the lone Japanese-American during discussions on World War II history. The white man is always supposed to win somehow in history. They’re supposed to have done everything for a “good” reason, or “have learned” from their mistakes and will never talk about them again. That is white privilege inside the classroom.

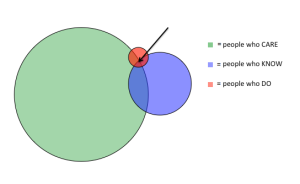

On a more macro-level scale, let us be reminded of the blog’s name – thirty eight minutes. That’s how much time a student averages with their guidance counselor over four years. That’s nothing. That’s the amount of time it takes to watch one episode of House of Cards. Are our children’s post-high school careers only worth the time of a Netflix original series? For POC and white students in poverty, this thirty eight minutes may be the only thirty eight minutes they have to learn about college, financial aid, vocational tech, financial responsibility, and community college. POC and white students in poverty have little to no access to outside help. Knowledge is power. Having a mother or father with a college degree does not just guarantee a higher income in the household, it guarantees someone that can navigate the post-high school process. Applying for scholarships or loans are taken for granted, but could be a complicated process for someone that has never experienced it before. The ACT isn’t even a fully objective standardized test – people with wealth can afford Kaplan classes or other similar outside tools to boost their scores and get scholarships from prestigious universities. The PSAT is a well-kept secret. Many schools do not prepare their students enough, despite the sheer amount of scholarships that can come from a great PSAT score. Additionally, the highest scorers are often the ones that could afford to prepare. Affording preparation for the ACT/PSAT is not by not just having money for classes, it’s having a stable family situation and food to eat as well.

Not only are students struggling to get into college, getting through primary and secondary school is an ordeal as well. POC, notably black students, have dealt with a notorious achievement gap starting early in primary education.

“Researchers consistently show that black–white gaps in educational achievement and attainment contribute to racial inequalities in health and mortality (Hayward et al., 2000, Pampel, 2009 and Williams and Collins, 1995), employment and wages (Cancio et al., 1996, Kim, 2010 and Grodsky and Pager, 2001), political participation (Logan et al., 2012), and crime and incarceration (Pettit and Western, 2004, ), among other major life outcomes.”

– S. Michael Gaddis and Douglas Lee Lauen. “School Accountability and the Black-White Test Score Gap.” Social Science Research44, (2014). 15-31.

From day one, impoverished, mostly black and other POC students, are behind. It’s hard to study when the only meals a student has are the school lunches. It’s hard to stay in school when a student is working two jobs or selling controlled substances to make enough money for their family. This isn’t to say that all POC are inherently just behind their white counterparts 100 percent of the time. Nor is this to say white students do not have their own interpersonal struggles. But this is to prove that equal opportunity does not always apply to everyone. Even for highest achieving POC and white students in poverty, they are not well-represented in public or private institutions. Affirmative action debates echo the naïve sentiments that racism is over, or that things “have changed enough” over the last 50 years.

There is no “equality of opportunity” in America, past or present. Let me repeat that sentence so you, the reader, will understand and come to terms with my conclusion. There is no “equality of opportunity” in America, past or present. The sheer naiveté of the American psyche to claim we are all equals is offensive. I am literally offended when people say all children have the ability to “follow their dreams” when children die in the (housing) projects and limited Tribal lands – the direct results of unfettered privilege ruthlessly exercised. The only way our society will truly be the “post-racial” society that individuals claim America is starts with transcending this illusion that all Americans are currently equals. We are not equals. Ask the transgendered black women. Ask the southern gay males. Ask the black boys in Milwaukee. Ask the rape victims. The beautiful thing about the human race is that we are capable of being equals. But we have to want it. And more importantly, we have to challenge the systems that keep us from having equality. We have to have courage. Americans have always had the minuscule amount of courage it takes to hate. Let us find the great amount of courage it takes to admit our institutions are wrong, and that we must love each other equally.