A Break from Our Regularly Scheduled Programming

By Aaron Bumgarner

Having read a book about Katrina hardly makes you an expert on Katrina or New Orleans or hurricanes. But you learn enough to see that being an expert hardly means you make all the right decisions. Five Days at Memorial covers one New Orleans hospital’s ordeal before, during, and after Hurricane Katrina hit. The hospital was named Memorial Medical Center, and it received national media attention after Katrina for accusations of doctors and nurses euthanizing patients during the disaster. Author Sheri Fink is meticulous and thorough in her reporting, giving detail to the lives of everyone affected and making clear the medical, legal, and political bureaucracy involved at every stage.

The most fascinating section of the book is also the most heartbreaking, the five days at Memorial, when the hurricane hit. We get an intimate look at the horrifying conditions and the desperate doctors, nurses, and patients fighting for survival. The hospital didn’t flood completely, but enough that some of the electricity was knocked out and the heat became sweltering.

Taking care of the patients became increasingly difficult to the point that some patients appeared to be suffering on the verge of death. This hostile environment, coupled with the unwilling ignorance of the volatile situation in the city outside, presumably contributed to the tragic decisions made to end patients’ lives without their permission.

Fink writes that it was later revealed that some of the more senior doctors had taken some breaks from the hard work of caring for patients and running a hospital in crisis by retreating to a part of the hospital unaffected by the storm to run fans and watch TV. Somehow they failed to suggest that the patients be moved to this more amenable environment or that the hospital’s overworked nurses seek similar respite.

Pop Culture and Katrina

Five Days was released at a curious time: in 2013, eight years after Katrina. After you read the book, though, you appreciate the utter immersion Fink endured to tell the full story, and eight years seems surprisingly brief. But in all that time, there’s been a surprising dearth of popular culture dealing with Katrina. Fink writes about one prime example most relevant to Memorial, an episode of Boston Legal, of all things, in which the court rules in favor of a doctor who euthanized patients during Katrina. Some that I’ve encountered include the homemade movie Trouble the Water and the epic non-fiction Zeitoun by Dave Eggers. And of course, there’s Treme, the inscrutable HBO show by Wire genius David Simon.

There’s just not much out there, which I suppose shouldn’t be too surprising. America has exhibited a disturbing trend recently of not processing its tragedies in its art. This goes for 9/11 too, of course. When trailers for United 93 played in theaters, there were cries of “Too soon!”, though it was released five years after the event. We now only allow our major filmmakers to make movies about the wars we’re in overseas, not the disasters within our own borders. And that’s only true if they’re marketed as heroic victories, even when the stories they tell are morally ambiguous cautionary tales.

I say all this not because we can’t handle the truth. We handle it just fine when the narrative is packaged nicely for us, such as when the Saints won the Superbowl in 2010 and it was painted as a win for the Katrina-ravaged New Orleans. That Saints win was important; it provided hope at a time when hope was still hard to come by. But that’s not the only function of pop culture. Art should also be able to shine a light on misdeeds so we can learn from history and do better next time. The fact that popular art has ignored Katrina isn’t unexpected, but it is unacceptable.

Learning for the Future

Five Days at Memorial received a lot of attention last year. It won the National Book Award for non-fiction and appeared on the New York Times Best Books of 2013 list. The story has been optioned for a movie by Scott Rudin, producer of The Social Network, Moneyball, and Captain Phillips. Those may be the best movies you could want as examples for the kind of quality this story deserves.

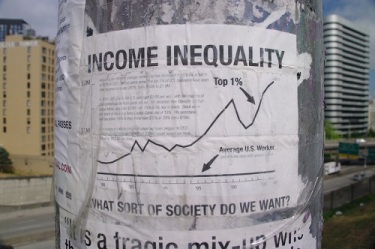

Popular culture doesn’t solve problems, but it does teach. Five Days at Memorial is an instructive book, but movies obviously have a higher profile. When popular culture engages with current events like this with a high level of public exposure, then regular culture has no excuse. When catastrophe strikes again due to a failure of bureaucracy (like, say, an Ebola crisis), learning from disasters like Katrina is what will save us. If we don’t learn, it will look much like the above episode from Five Days, in which the nurses and patients suffer in the heat and the doctors relax in cool air conditioning and watch TV. It will be the poor and underprivileged who suffer the consequences.

—-

Aaron Bumgarner is a speech-language pathologist for Oklahoma City Public Schools.