By Lester Asamoah

2016, in some ways, has been a rough year in America. Racial tensions seem to be at least as high they were in 1992 after the Los Angeles riots. Some older civil rights activists even claim that tensions are close to as bad as they were during the civil rights movement. Race relations haven’t been the only divisive issue by any means – LGBTQ+ and Muslim issues also have had major dividing points. Needless to say, 2016 is a year in particular where it’s worth discussing these issues. Even if it means repeating certain issues or points. I’ve largely abstained from writing about these issues, but I want to return to them.

On Twitter, I’ve said that when I see certain politicians talk, I feel like I live in a different America than them. To be clear, there’s nothing inherently wrong about having a different experience than someone else in the same country. I’m sure that someone living in San Francisco, CA has a fundamentally different experience than someone that lives in Savannah, GA. However, there seems to be major gaps in how some of the fundamental problems America faces is approached. We have different problems and perspectives. Again, not inherently bad. But some of the problems faced by certain Americans goes largely ignored. This election cycle along with other major events in the [US] country have revealed our capacities to misunderstand each other.

This isn’t the part where I say we should all get along and end the post. I wish it were that easy. This is actually the part where I try to tease out of some of what I think can help develop basic understanding between our different experiences.

Listen and Share the Load

If you’re at all interested in what people are marginalized in America are going through, you should start by listening. I say this time and time again. But, ironically enough, people don’t seem to listen. Or they need to be reminded multiple times. I also suggest listening to things from people of the particular affected group. It makes no sense to hear a congressman pontificate about how bad the shooting was in Orlando – especially if they don’t mention LGBT people (many people did not) and if they’re not LGBT themselves. This isn’t to say that people of the out-group can’t have opinions, but it seems asinine to build your opinions and advocacy from the words of those not in the marginalized group. A certain presidential candidate addressed the black community in a city and crowd that is overwhelmingly white. What good does that do?

If you’re a good listener, then you won’t have to ask the same questions over and over again. As Toni Morrison and many others point out – a part of oppression is having the marginalized consistently have to prove themselves and help others understand what they’re going through. Unless you’re asking a real simple question or are willing to start an honest conversation about a social issue, don’t keep asking basic questions. Google is a hell of an invention. Don’t waste people’s time forcing them tell you about racism, sexism, ableism, Islamophobia, homophobia, etc. when you have the resources to learn about these issues. And if you don’t have the resources, then make that clear. And make no mistake, if you’re intentional people will be receptive. But just know that when you see injustice and you keep saying “I didn’t know, I didn’t know,” it really does no good for anyone. It also does no good to call someone/group of people stupid for what they believe in. Even if you think they are, constantly sharing articles about how inferior a group of people are to you and your cadre of friends isn’t ingratiating. Oh, and let’s stop with the damn “devil’s advocate” please, unless you like patronizing people. We don’t need anymore devil’s advocates.

Changing from Within

Do you believe that people can change? Well, to some extent, people have to change for there to be less tension in the US. As alluded to previously, people have to change the way they take in information about others. But internalizing it is just as important – how many times have you sat in front of a TV or a lecture and not remembered anything that was said in the last 5 minutes?

It’s incumbent of us, as Americans, to get to know the other side. Of course, this shouldn’t be done if the other side is hateful or harmful to our health. I strongly take the stance that I shouldn’t need to empathize with the arguments behind racism, homophobia, and Islamophobia. Thinking people are inferior based on race, gender, religion, etc. isn’t okay, and we shouldn’t be interested in entertaining those beliefs. But where can we as individuals help others move on how they view the world? Can we help people move on these issues? I’ll be honest – I don’t have a great answer because I believe in spending energy on keeping oneself healthy and prosperous; battling with someone who sees you or others as less than a fully valuable human goes against that. Alternatively, what are we doing within our in-groups on these issues? The black community has pressing issues of misogyny and homophobia to deal with. As do many other communities of color. Intersectionality is something that has to be practiced by everyone.

To put this bluntly: for there to be change, the people that are in the dominant group have to change. For systemic racism to end, white people have to change. For misogyny to end, men have to change. For Islamophobia to end, people who are non-Muslim have to change. For homophobia to change, straight people have to change. You likely get the point now. This is where intersectionality is critical because a lot of us in some way belong to a dominant group. It’s not enough to say only white people or black people should change. And it’s definitely not enough, if not pretty offensive, to say that someone in the marginalized group should change – i.e. lesbians should “act straight,” blacks should “commit less crime.” Just for the record: lesbians should act however they please and we shouldn’t assume blacks are prone to committing crime. Rinse and repeat these principles.

Free Expression

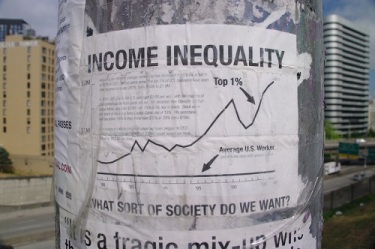

So if a problem is that we’re bad at listening and internalizing important things about those different than us, we should expect people to get mad sometimes. Of course, it does no good to endlessly scream at someone about an issue. But anger is a legitimate response to being called rapist by a certain political candidate based on arriving from a certain country, or seeing people that look like you getting shot down in a Florida nightclub or in the streets of Milwaukee. For some reason we just have a hard time in America with understanding the emotional responses of others. We need to get over that. We need to understand the varying expressions of those around us. White working class people in Indiana who feel betrayed by the economy have a right to feel mad. Black students who are tokenised for 3 years of school at a predominately white institution [PWI] have a right to be reserved. LGBTQ+ people have a right to be annoyed at straight people constantly disregarding their rights (we do it way too often, fellow straight people).

Expression is an important point because when you press people in some way, they will eventually express how they feel. The inability to listen and learn means we have routinely misunderstood these expressions. And make no mistake, we as a nation will continue to misunderstand these issues if we don’t listen and learn.

…Is that all?

I promise I’m not trying to insult your intelligence and be elementary by suggesting we should simply “listen and learn.” However, that is that solution and we are bad at it. Quite frankly, it’s much easier to put off the problem for a number of reasons: we have our own things going on, we have a friend of a marginalized group that doing well so things are fine, or we just worry that we’ll never know enough to do anything. Those are things that I’ve faced, and things that I imagine most readers face. We have to be honest with ourselves. It’s easy to write Facebook statues and call it a day. It’s easy to let that guy we know say the n-word. It’s easy to let a sexist joke slide. But it’s difficult to confront ourselves and these small battles. And sometimes these battles are more harmful than good. Sometimes we lose friends. Sometimes we need breaks. But if we’re concerned about bridging the gaps that have made America feel so divided, we have to do the work and that’s where the work is. Don’t say I never warned you.

—

Lester Asamoah is a graduate student at American University.